Extract from a zoom talk

This is an edited version of a talk I gave to a cohort of artists from in and around Derby. Some established, some emerging – all keen to engage with new modes of digital art making.

Introduction – process & access

For the past ten years or so, both as part of my PhD research and through freelance associations with theatres and performance labs, I’ve been lucky enough to work on many events that connect audiences and performers through technology. Whilst these events might each be radically different in form, duration, and structure they are often clumped together as ‘digital performance‘. This is a kind of useful (or at least well known) shorthand for any kind of work that incorporates new or novel uses of technology.

That decade of learning and doing includes a long stint at Contact Theatre in Manchester, at a time when it was making a concerted effort to engage with digital practice. One key pillar to developing new digital and remote performance has to be the building of relationships with other institutions and artists. The most important connection I made during that time was with New York based technology lab Culturehub, itself born out of a long term collaboration between the experimental NY theatre space LaMaMa, and the Seoul Institute of the Arts.

This almost perfect alignment between the theatre’s desire to make new digital work, and my developing practice, made this a great opportunity to engage with, learn from, and work with pioneers in networked performance. We’d use new media tools and video conferencing gear to create hybrid stages, with performers and audiences in different cities sharing the same experience, defying geography.

During that time I was given support and space to prototype and develop new streaming and video techniques. Alongside the theatre’s production team, I’d work with visiting artists and new partners from different countries – experimenting both with new technologies and methods of collaboration.

I’m still in touch with the folks at Culturehub, and am watching with interest as they produce new work during these pandemic times. Of particular interest is their new online media system Live Lab, which is open sourced and free to use.

Transporting performers through technology is not just a way to save on the air fare. Working with disability-led theatre group Proud and Loud on their show Pyramis and Thisbe, we trialled telepresence technologies as a means to bring performers to the stage who might otherwise be unable to come on tour. This might be due to a performer’s particular care needs, or maybe that the show was touring to a difficult-to-access performance space.

Using technology in this way can provide a living, two-way connection between performers both at remote sites and in the theatre space itself.

During this period is also when I began to work with access tools for streaming content. This work includes figuring out different ways to provide live captions, working with interpreters, and adding audio description tracks.

incorporating dedicated BSL cameras and live-captions supplied by Stage Text.

Much of this prototyping did not find its way into the theatre’s practice, but it did make it clear that by making the work accessible, you simply make better work. Also, that the cost argument is one of choice, not inevitability.

I’m rather taken by the phrase “Budgets are moral documents” which I recently heard via Action Hero on twitter, although I believe it has been around for a while and has been, at least apocryphally, attributed to Dr King. For me, it cements the idea that access budgets should be built into all art making from the institutions down.

When making that work in digital and online spaces collaboration is fundamental. I make a point of mentioning this. Somehow it’s particularly easy to work in a silo on digital projects, when it seems that the opposite should be true.

I think that right now, new collaborations and conversations are happening between artists with wildly different backgrounds. The crisis of the pandemic has forced us to find new ways of working and making together. I hope that because of this, we will learn how flexible and porous the boundaries between these disciplines can be.

Stories shape the way we exist: with a deft blend of logical step-by-step and a rush of emotion, they hold authenticity and truth within them. But these truths are contingent. And at this moment in time it is very difficult to imagine telling stories in the online space, without also thinking about the technologies that make them possible. Technologies that, far from being ethically neutral, exist within the frameworks and structures that perpetuate the status quo.

Raymond Williams suggested that technology does not come into society as a radical change maker, or as a harbinger of change. Rather, it is the capitalisation of technology that brings it into common usage. A colonisation of the new by the already dominant ideology.

New platforms for stories aren’t neutral.

This is not to say that we can’t build radical stories within existing structures. Artists are eminently capable of bending structures to their will, to discover the edge cases and grey areas that even the developers of virtual spaces have no knowledge of, or interest in. Yet, the stories we tell using online and digital tools are as much an interrogation of the spaces we tell them in, as they are of the characters in the stories themselves.

And maybe it’s our duty to reveal how the technology influences the telling, how the infrastructure drives the story, and determine who takes part.

Artworks in a lineage

It often surprises me how the category of digital seems to pop up as though it’s something quite new and different: the digital strategies of government and brands, the arts centre, theatre or gallery offering up a new season of digital works. As though digital or online activities haven’t already intertwined so successfully with our lives that it would take some huge effort to untangle them. Designer and urbanist Dan Hill says:

‘Technology is culture; it is not something separate; it is no longer “I.T.”; we cannot choose to have it or not. It just is, like air’

Dan Hill, 2013 – link

More than 50 years ago, media artists were already subverting performance and technology to create new hybrids. When I was a teenager, artists were experimenting with video systems to create stages that spanned continents. The last twenty years or so have seen huge leaps in the development of digital communications technologies, AR, VR and 360 capture – many of these technologies are now widely available at low cost.

They have become second nature, part of our everyday.

I’ve written about a few of these artworks before, so you might want to skip any you already know about :-)

Hello (1969)

Back in 1969 Allan Kaprow’s Hello was made as an ‘interactive video happening’ as part of the TV show The Medium is the Medium broadcast on local TV in Boston.

It used the TV station’s closed-circuit, outside-broadcast system to connect four locations using five cameras and 27 TV monitors. Groups of participants were sent out with instructions to perform actions based on what they saw through the monitors: maybe saying “Hello I see you” when they saw an image of themselves or people they recognised. Kaprow directed, switching the images the monitors displayed from one camera to another. Becoming the conductor of a technologically mediated, wide-area game of tag.

Using the close-circuit of the TV infrastructure Hello short-circuits the TV network, highlighting the potential for human to human connection, rather than the broadcast mode it normally operates in.

Asking the question who gets to be seen.

In this new Zoom-time, where hook-ups, birthday parties, family quizzes, weddings and even theatre is being constructed in real time over the screen, it would be crazy not to mention one of the most “celebrated examples of pre-Internet, telematic performance” the Hole in Space.

Hole in Space (1980)

Created by artists Kit Galloway and Sherrie Rabinowitz in 1980. Hole in Space used borrowed satellite broadcast technology to open up a “virtual tunnel” between The Broadway department store in Los Angeles and the Lincoln Centre in New York City.

With cameras and screens in both locations, live feed from one location was back projected in black and white and at life size into the other. Audio was also transmitted, allowing passers-by an unprecedented way to communicate between each other thousands of miles apart.

It was only up for three days, yet new relationships were struck up, people returned each day to see and chat with each other. Relatives and friends in the two cities made arrangements

to meet up through the artwork. It became influential both in the arts and technology worlds.

Streaming audio and video between different places to create an artwork is just about as old as the technology itself.

We’re drawn to platforms or systems that are designed for theatre or gaming, with their ready made toolsets and protocols. Yet there is also some fascination in creating artworks in places they are rarely to be found. In the everyday technological spaces we use to communicate with each other, where we share fragments of our lives from the trivial to the life-changing.

You With Me (2012)

Kaleider’s You With Me is a one-to-one audience experience which takes place entirely within a 45 minute telephone call. The performer and participant never see each other, and hear each other’s voices only through the phone.

For the participant, the call shifts between different styles of conversation. At times as playful as a game, at others contemplative and reflective, almost therapeutic. For them the work feels relaxed and open, which shows how deftly hidden its tightly scripted structure is.

There is orchestration too, a whole team of observers and facilitators keeping the performer grounded with information about the movements and actions of the participant. This feeds into their improvisation, bringing a kind of ‘how did they do that’ magic to the game.

The structure of the call begins with some simple instructions, turn left here, go north. This swiftly becomes a game of hide and seek: ‘try and lose me’ says the performer. This starts a breathless chase through a crowded city. This game of chase can’t really be won or lost, in most cases the participant remains under surveillance, but some are too darn good at hiding or running, and manage to escape. This, too, is folded into the hugely improvised work, escape is a rush whilst being tracked by an unseen voice is sorcery.

Once the game of chase is over, the participant is invited to “share a drink” with their performer. Not physically in the same space, but each wherever they are. Maybe it’s the aftermath of the adrenalin rush of the game, but at this stage the interaction between performer and participant will edge towards ‘the conversation in their lives that they are not quite having’

Led by their performer, the participant ends up adrift in time and space. Being gifted this moment to make conversation with a stranger, someone they will almost certainly never meet again.

The infrastructure of the piece provides a place for fragmentary stories to flourish, for deep emotion to come into play. This is a form of mediated intimacy, an exposure of self and the sharing of private information made possible by the limits and the parameters of the performance and the technology.

Life Streaming (2010)

In 2010 theatre maker Dries Verhoeven created the telematic artwork Life Streaming. Using video conference technology it connected two groups of people, in two physically distant locations.

To take part, twenty participants are asked to take off their shoes and enter a specially constructed trailer kitted out as a kind of mobile Internet café, sited outside the National Theatre on the banks of the Thames. Now sitting at twenty computers, and using bespoke software, they are connected to twenty performers some 8,000 kilometres away on the coast of Sri Lanka. That same coast where a devastating 30,000 people lost their lives in the 2004 tsunami.

Curtains are lowered over the windows of the London trailer, and the participants are sat at booths with wooden walls to blot out any peripheral engagement with the local environment.

Through scripted and improvised scenes, the Sri Lankan performers reveal personal details of their lived experience to the unsuspecting, expectant audience. Using improvisational techniques they encourage sharing and conversation.

‘The performance only worked when the spectator felt that this part was “live,” that his answers were meaningful and were taken seriously and that the performer was honest to him, both about his personal life and about the structure of the piece’

Dries Verhoeven (2012)

At the end of the piece, as the Sri Lankan performers run toward the sea, the participants in London feel the uprush of warm water as the lower part of the trailer is flooded. They share this embodied experience born from a virtual one.

This encounter operates as ‘part travelogue, part Chatroulette, part carefully crafted cultural and moral lesson’. Yet the level of intimacy and connection that it created often continued after the performance, with audience members and performers messaging each other long after the show was done.

Win, Place or Show (1968)

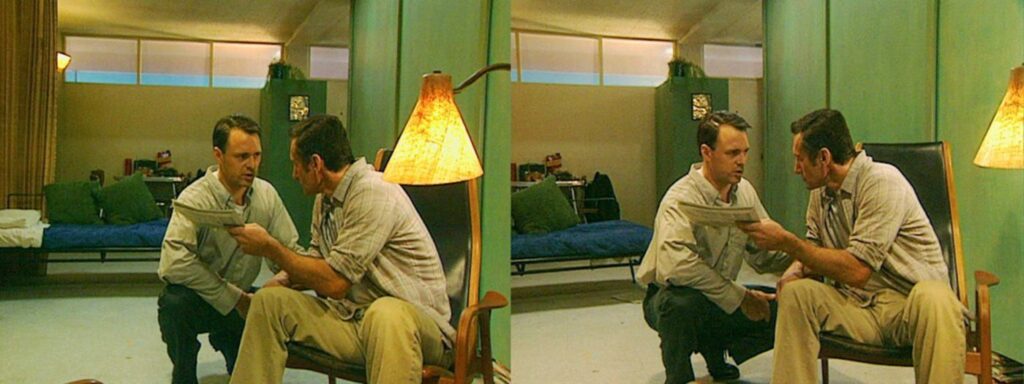

Nearly 20 years ago I was walking through the newly opened Tate Modern. My friends and family wandered all over the gallery, but I stayed in one spot. I’d stumbled on Stan Douglas‘s “Win, Place or Show” and I was transfixed.

The description runs: “Donny and Bob, the two men in Douglas’s video installation are caught in a perpetual loop. The action repeats every six minutes, but the particular shots taken from multiple cameras are selected randomly by a computer. The same sequence will only occur once every twenty thousand hours”

The repetition is Douglas’s nod to the playwright Samuel Beckett, but it’s also a challenge: no performer can repeat their action as precisely as these recordings. The same events happen slightly differently, time and time again.

Unlike most of the other work I’ll talk about today, this installation is not performed live, but somehow the way it’s put together seems to feel almost like it is.

The artwork continues to play with or without an audience, and as I leave the room it feels like it’s always been playing, and always will.

There are many tools in the digital toolbox. These tools can act as nodes within complex workflows. Combinations of software, hardware, humans and networks generate new spaces, and find new ways to connect performers and machines with audiences and participants.

Graphic Ships (2014)

In 2014, at the Fascinate conference of arts and technology in Falmouth, I was the guy on the ground helping culturehub veteran Jesse Ricke stage his interactive, networked performance Graphic Ships.

This project uses video conferencing hardware, a Kinect motion sensor, the MAX MSP software environment, and a robust internet connection to bring together musicians, performers and audiences in a single performance.

For the event in Cornwall, a lone dancer performs on the stage in Falmouth’s town square, her movements are tracked by the Kinect sensor and translated into graphical shapes in real time using custom software. These shapes, this graphical score, is screen shared with six musicians themselves located in New York, France and the UK. The musicians play to the score, and their music is amplified by the PA here in Falmouth, whilst their images are projected on the buildings that surround the square.

The dancer, Sara, moves in time to the music her movements create.

Airlock (2020)

The theatre company imitating the dog have been playing with the combination of live camera feeds intermixing with performers on the stage for more than two decades. So coming into lockdown it was no surprise that they would create a new piece of work which would combine their technological expertise with the video platforms we’ve suddenly all become hyper-familiar with.

This new piece is made in real time using the media processing software Isadora. Textures and loops created in Photoshop and After Effects are layered and composited with live action cameras in real time. The show was originally designed to be performed live to an audience, each performer beaming in from their own lockdown home, one particularly hot and bothered Mac Pro performing the cue to cue magic, turning Skype calls into comic book frames.

Every episode made in a single take.

At some point during the development of the piece the company was offered a slot on iPlayer, and audience reach trumped in-the-moment liveness. Nevertheless, this is a great example of how its possible to bend tools and workflows to the demands of live, digital performance.

Each of these artworks engage with technology in quite different ways, although all strive to make contact between artist and audience. Through the making of art and the experience of artworks created with digital tools, we are finding new ways to connect with each other. Expanding our understanding and empathy through the digital day to day.

Want more?

Here are some of the companies doing amazing work in this field:

Coney – https://coneyhq.org/h/

PVI Collective – https://pvicollective.com/

Hidden Track theatre – https://hiddentrack.org.uk/

Fast Familiar – https://fastfamiliar.com/

Blast Theory – https://www.blasttheory.co.uk/

Some interesting and off/beat ways to work with technology …

Videos & Audios:

Builder’s Association, Continuous City

Alex Kelly‘s Playing Detective (A live recording of a radio play)

Forced Entertainment‘s Void Story

ProtoType‘s Whisper – http://proto-type.org/archive/whisper/

Cardiff / Miller – Video (and audio) walks

Rimini Protokoll – Situation Rooms – http://www.rimini-protokoll.de/website/en/project_6009.html

StationHouse Opera‘s

Play on Earth & Roadmetal, Sweetbread

http://www.stationhouseopera.com/project/6048/